The Great Fire Engine Mystery – the story

It’s Good Friday – the one day in the year that the workers in the village have as holiday.

But, Chief Engineer Rab Bit and his team have to test the fire engine.

Disaster strikes as Rab is walking to the village through the woods. He steps on a rabbit trap. He drops his notebook. He manages to escape but his leg is broken. He can’t organise the fire engine test.

His team do their best.

They wheel the fire engine down to the village pond. They put one end of a hose in the water. They hold the end of the other hose up towards the trees. They start pumping. Everyone comes to watch.

A great cheer goes up as the water gets to the top of the trees. The fire engine is working.

But suddenly they hear a scream. Mummy Duck comes running up. Duckling is missing. One minute he was taking his first swim in the pond. The next he was nowhere to be seen.

Whatever happened? And where is Duckling?

Crack Reading detectives are called in to look at the evidence.

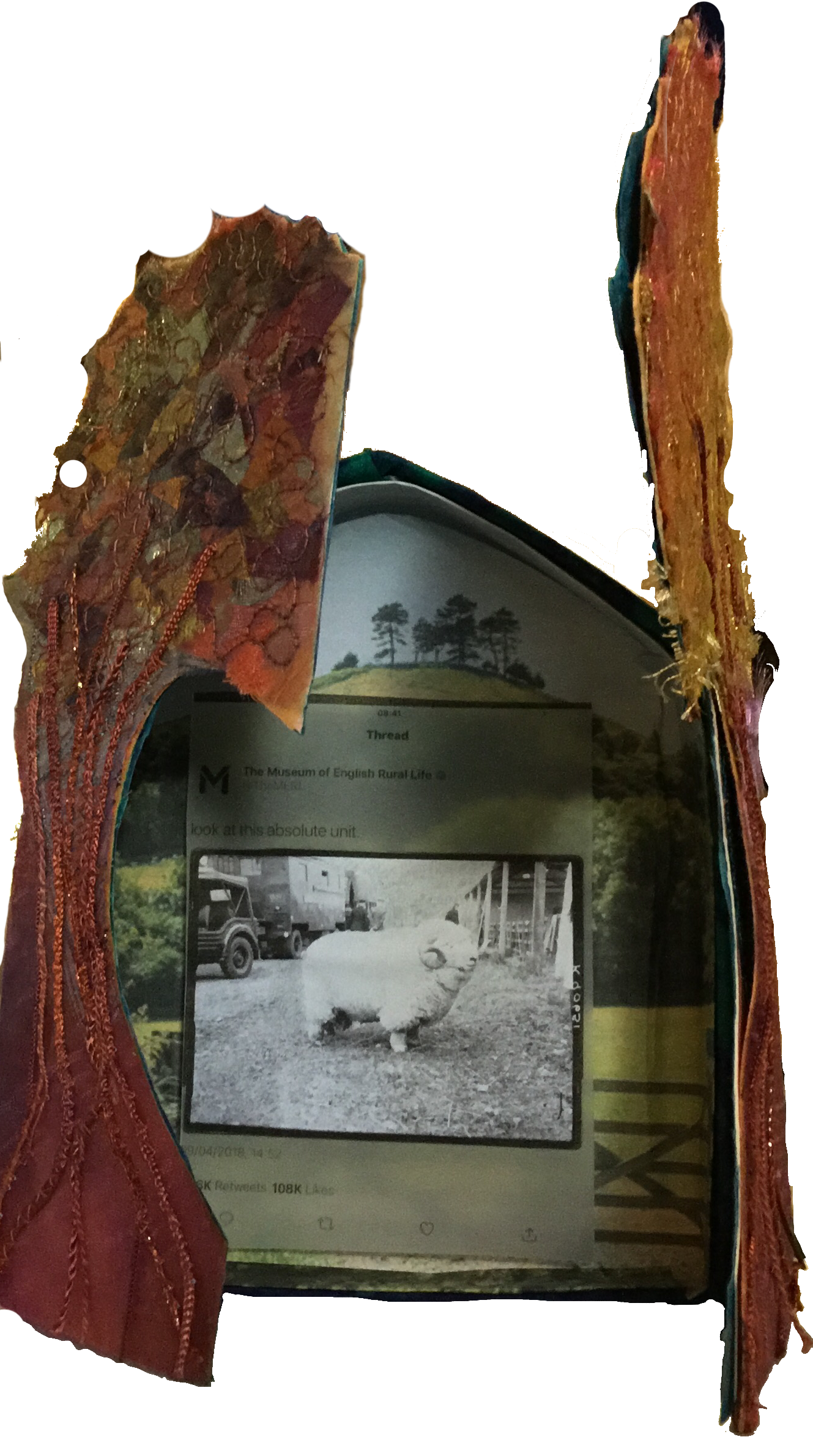

Some children by the pond thought they saw something fly past. Luckily one of them has taken a video on her phone. The detectives have a good look at it.

https://www.youtube.com/BdkHuhTxBeM?

Is that Duckling zooming past? It can’t be. Duckling can’t fly yet. He was only just learning to swim.

The detectives find out how the fire engine works.

Was Duckling sucked up by the fire engine? But that should be impossible. A fire strainer on the end of the hose would have stopped anything being sucked up.

They find Rab Bit’s notebook where he’d dropped it by the rabbit trap. He had made a note to take the fire strainer with him.

The detectives hunt for the fire strainer. It looks very new and completely unused.

The detectives have discovered that the team forgot all about the fire strainer. Duckling must have been sucked up by the fire engine and shot out of the other end towards the trees.

They hunted high and low. Eventually they found Duckling, looking very angry, high up in a tree.

Mummy Duck was very happy.

The fire team were rather embarrassed but they never forgot the fire strainer again.

Chief Engineer Rab Bit was so grateful that he gave the detectives a medal and tickets to watch his favourite film, Tilley and the Fire Engines (1911).

…………

The not-so-Alternate Reality

Built in 1839, the fire engine at the Museum of English Rural Life, Reading, UK was in service for over a century. It was tested on Good Fridays as that was the only day, apart from Sundays, that the people in the Norfolk village did not have to work. Testing it was a spectacle that everyone came out to view.

Privy photo courtesy the Ramsey Rural Museum Cambs

A Chief Engi

neer and two other men were paid a small amount to tend the engine which was last used on a call to a privy fire in 1930.

neer and two other men were paid a small amount to tend the engine which was last used on a call to a privy fire in 1930.

The village decided it was too expensive to keep the fire engine in the 1930s but during the Second World War it was positioned by a farm pond in case incendiary bombs hit the hay ricks.

Further information about the fire engine is in the Museum of English Rural Life catalogue http://www.reading.ac.uk/adlib/dispatcher.aspx?action=search&database=ChoiceCollect&search=object_number=’51/410′

Just as we were setting-up the trail in the Museum, Fred the Conservator showed us a wonderful Huntley & Palmer biscuit tin. Dating from the 1890s, the tin depicts a steam-driven fire-engine drawn by two horses, with lively scenes of fire fighting. Fred kindly put it in the horse-vet display case near the fire-engine. Fantastic real-time museum display design! Huntley & Palmers was a central part of Reading life in the 19th and 20th centuries, and Alfred Palmer built ‘East Thorpe’ (Later St Andrews Hall) which now houses the Museum’s extensive archives.

Fred also found a video showing a fire engine like the one in the MERL being pulled by a horse in the Netherlands.http://www.brandweerevenementen.nl/Videos/MOV02419.MPG

and there’s another Tilley engine being demonstrated in New Zealand at http://youtu.be/2Ed39zcO84Y